1998 Riot - My Story

- Charles Marantyn

- Jun 27, 2025

- 6 min read

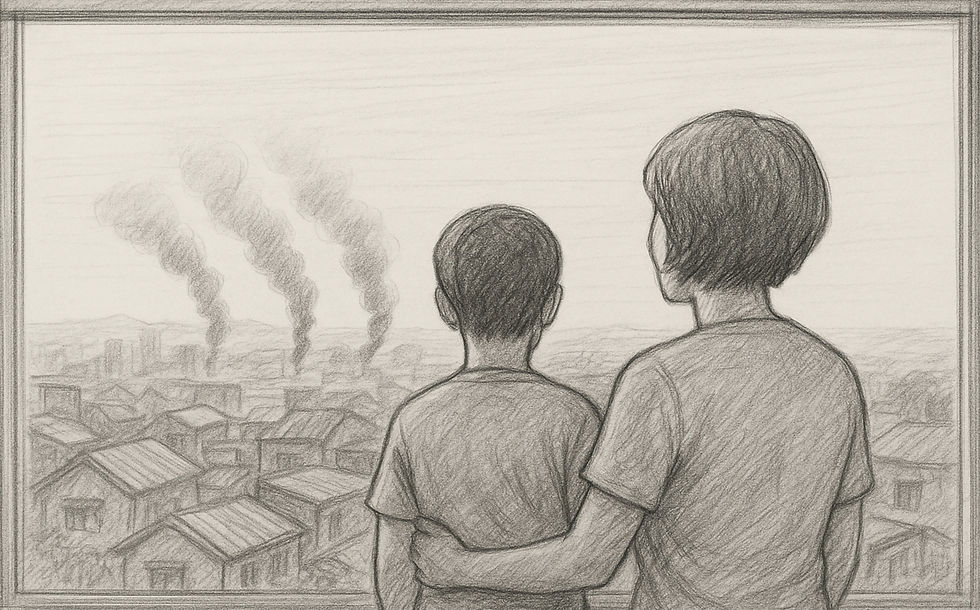

Here I am, sitting on top of Thamrin Nine with my mom, both of us irritated over a certain government man trying to deny the atrocities that happened to Chinese Indonesians. As I took the last sip of my coffee, the conversation slowly drifted from the man she was upset about. I told her not to get caught up in political commentaries, they’re designed to provoke, to stir public reaction. Don’t take the bait, I said.

Instead, under the sweltering heat of Jakarta, we started reminiscing old times, specifically, what happened to us during the riot.

I was 10 years old when it happened. I remember a lot from my childhood, I had a happy childhood, but some things are burned into my memory more than others. I remember snitching on my sisters when they went on dates. I remember destroying my mom’s kitchen decor playing near the stove. I remember crying on Sundays if I missed Doraemon. I remember the food my dad brought back from the market before work. And I remember the few times I kept our house from burning down.

The first time was when I caught a candle burning through my mom’s satin sheets. The second was when sparks shot out from cables around the house. Both times, I called for my dad, not my mom, because I knew she'd panic, and he’d reward me handsomely. I got a gaming console, a stack of game cartridges, and the rollerblades every kid dreamed of: a pair of California Pro.

They called me the lucky child.

On the day of the riot, I was home with my mom. My sisters were either at school, or dating, who knows. I don’t remember the exact time, but my mom was cooking and I was playing Crash Bandicoot on my Playstation. I was sitting on my red round bed (which I wish I still had) when I heard something. My room was on the fourth floor, and our house was the tallest on the block, so I had a clear view of the neighborhood.

I walked to the window, curious, and what I saw that day has never left me. The chaotic skyline of our neighborhood was broken by columns of smoke. I was a shy, cowardly kid, but that scene didn’t scare me. It made me curious. I kept watching until I saw droves of men, mostly buzz cuts, marching and shouting through the streets. That’s when I knew something was off.

I ran to the kitchen where my mom was, and she picked me up and approached the windows. In an instant, she put me down and told me to pack my stuff that was important. As a 10 year old boy, it was my Playstation, Walkman and somehow a black t-shirt with Lady Liberty on it. I rushed to my room and packed while my mom scattered downstairs.

I caught up with her and could see she was panicking. That made me nervous, but I knew I couldn’t cry, I didn’t want to become another problem. She was crying on the phone. My dad showed up with bags, and that’s when everything turned ugly. People started banging on our front gate. Our housekeepers were shouting downstairs. I don’t remember what they were saying, all I know was, in the next minute, my parents pulled me downstairs and we had to evacuate through the back door.

Our backdoor led to a small alley, and the next I thing I remember we were escorted by several men and my mom was now wearing a hijab. My mom was still crying, and I remember looking at her, feeling sad and helpless.

I didn’t feel like a lucky child that day.

We were told to wait at an office, I don’t remember what it was for, only that it became a temporary shelter with a few other Chinese families, some of them crying too. I was busy trying to make my mom feel better. After that, everything was kind of a blur until one of our workers picked us up and brought us to our other house nearby, which was part of our garment factory.

On the way there, we passed wreckage and chaos. Everything looked broken and looted, including our own house. My dad told my mom that some of our neighbors had joined in looting our home, which made her cry even more. Perhaps she thought that the people who used to wave at us, were now taking our things. That betrayal hit harder than any stone ever could. I remember thinking about my sisters, praying that they were safe.

When we got to the other house, it was lockdown. I don’t remember much of what was happening outside, I mostly stayed in my room. I remember being reunited with my sisters after, which made me really happy. I remember men keeping watch outside at night. I also remember a conversation about putting a signage outside our gate that read: Rumah Pribumi. In English: “Native House.”

What happened after that is mostly a blur. I suppose there’s something about knowing your family is safe, it shuts your brain off like a defense mechanism. My body stayed alert, but my memory just stopped recording. No more burned images, no sharp moments, just a numb kind of stillness.

The next memory I have is driving to the airport, we were on scheduled to fly out to Pontianak. The journey to the airport seemed like a scene from zombie apocalypse. I remember seeing cars abandoned on the highway, and it was as if time had frozen.

The horror didn’t end in Jakarta.

One night in Pontianak, word spread that a mass of people were planning to “sweep” the Chinese neighborhood where we were staying. I didn’t understand what that meant, not really. But I remember my sisters putting on layers and layers of clothes, one after another. As a 10 year old boy, it looked strange to me. That night, we all stayed in the same room. No one said much. I think I fell asleep, eventually.

After that, my parents made the decision to relocate the whole family to Malaysia, like many Indonesians did back then. We moved from hotel to hotel at first, then finally rented a house to settle in. My mom stayed with us in Malaysia in the early days, while my dad was still in Jakarta, protecting his assets.

I couldn’t speak English back then, not properly. I had to attend language tutoring before I could even step into a real school. That was also where I learned to ride a bicycle.

A strange, simple victory amid everything else.

Eventually, we all settled nicely in Malaysia. My mom had to return to Jakarta to be with my dad, so she left me in the care of my sisters. There was a brief moment when I was placed in a guardian’s home, because my parents weren’t sure my sisters could take care of me on their own. But after what happened, I pled to my mom that I’d rather be with my sisters, so I was returned home to my sisters.

Still, somehow, we made it. I was admitted into an international school and my sisters joined private colleges. We made friends, and my parents would come and visit. Over time, it stopped feeling like a refuge and started becoming home.

Even with all that we went through, we were the lucky ones. We survived and we stayed together. That alone makes us “lucky”. Because many others, those Chinese families whose names will never appear in textbooks, were denied that fate entirely.

Looking back, I sometimes wish I could go into the past and take those memories away from my parents. Not mine, but theirs, because they lived through it in full color. They worked hard for everything, built everything, only to watch it burn in front of them, and somehow, they still had to move forward protecting us from the pain and trauma.

So when a man, a man whose face, frankly, resembles a frog more than a leader, dares to say that nothing happened, that the Chinese were never targeted, never violated: I would like to invite him to come sit with my mom and dad at Thamrin Nine.

They’ll show him exactly where the smoke came from.

Comments